Social Determinants of Health: How Privilege Impacts Health Outcomes

Our last blog spoke about the 4 Ways to Maximize Your Health. In that piece we talked about how little changes in exercise, nutrition, sleep, and stress management can have profound impacts on your overall health outcomes. And as much as we want to continue to emphasize the importance of taking ownership of your health, we also want to shed some light on the glaring, and unfortunate, reality that your health is largely impacted by forces outside of your control.

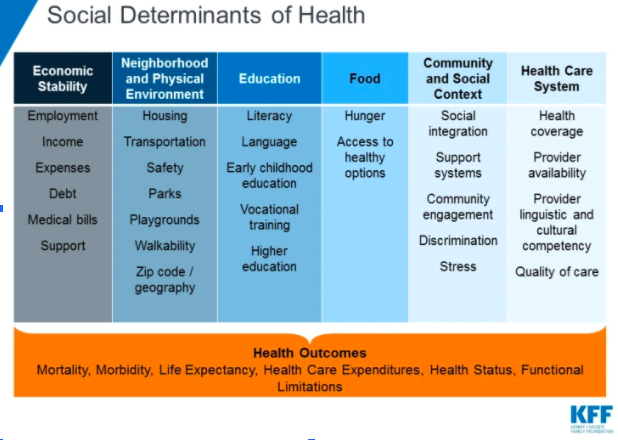

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), “The social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. They include factors of socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care.”

Figure 1

This is not a new notion - the idea that social and economic disparities contribute to poorer health outcomes in certain demographics. In fact, between 2006 and 2016 a total of 4779 scientific papers that mention the term “social determinants” have been published (Cockerham et al, 2017). Because of the magnitude of data it would be impossible to do justice to the entire topic in one blog post. However, we want to begin the discussion on the interlacings of health, wellness, and social inequality. And while we want to focus our attention on the issues within the United States we want to take a moment to point out that these issues are seen on much larger scales internationally as issues of poverty, sanitation, and education impact the livelihoods of people all over the world.

(The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change; Lancet - University of Oslo Commission on Global Governance for Health)

What do the data say?

A study published by JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) in 2016 found a positive correlation between income and life expectancy with a 14.6% difference in life expectancy between the richest 1% and the poorest 1% of the population (Chetty et al, 2016). Another study done in 2017 found a 17% mortality risk and a 48% disability risk in the lowest wealth quintile in the United States versus a 5% mortality and 15% disability risk in the highest wealth quintile. Without even getting into the various contributors as to why these findings are the way they are, it is clear that simply being poor is a threat to your health (Makaroun et al, 2017).

Multiple studies have also come to similar conclusions regarding chronic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and obesity (just to name a few): social determinants such as poverty and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) increase the risk of chronic disease throughout one’s lifespan (Cockerham, et al 2017; Sonu et al 2019).

So how did we get here? Why is it that the underprivileged and under resourced tend to experience harsher health outcomes just because of where they live and what their annual income is? The answer is that there is no clear cut answer. This is a multifaceted and extremely complex issue and we will do our best to highlight some of the broader contributors to what the World Health Organization believes to be a necessity throughout the globe.

Resources

All six of the categories mentioned in Figure 1 have some tie in with the challenges that those in underprivileged communities have when it comes to accessing resources that would be beneficial for one’s health. When one thinks about community healthcare resources the first thought is usually whether or not that neighborhood has a hospital. However, many other physical resources are often lacking in underserved communities that play a factor in one’s ability to maintain proper health. Some examples are as follows:

Grocery stores with affordable and healthy goods - grocery stores typically operate on very thin profit margins. This forces smaller food stores in lower income neighborhoods to primarily stock foods with longer shelf lives (often high in calories and preservatives) while increasing prices on fresh items. We speak of the basic need of adequate caloric consumption in athletes. The lack of sufficient caloric intake is a real issue in underserved communities.

Availability of physical activity programs for youth - schools in underserved areas often have smaller budgets for sports and afterschool programs and many families in these communities are unable to afford what programs do exist.

Jobs that provide adequate health benefits and wage standards that allow time for routine medical visits - working multiple jobs, working for low hourly wages, difficulty accessing healthcare providers, and lack of health insurance all contribute to the fact that those in underprivileged communities tend to schedule fewer routine visits and are less likely to trust and adhere to recommendations given by healthcare providers (Cockerham et al, 2017). Medical care is expensive enough for those with sufficient coverage. Suffice it to say that the costs can be insurmountable for those with lower household incomes.

Education

Navigating the healthcare system, understanding pharmacological instructions, and regular preventative measures all seem to be impacted by lower education levels. For example, the Commission on Social Determinants of Health found that those in the lowest economic quintile were less likely to receive their full schedule of immunizations. Many medical professionals argue that one of the most important, and life-saving, actions one can take in extending their life expectancy and overall health outcomes is to receive their full vaccination schedule.

It doesn’t take too much digging around to realize that education levels and earning potential are correlated and we have already discussed how income levels and health outcomes are related.

Stress and Social Support

An underlying social determinant that is not talked about as often is the chronically elevated stress related to living with less. From concerns of living paycheck to paycheck, the possibility of catastrophic events without an adequate savings, threats of violence from police or others in the community, and down to the stress of living in inadequate housing situations, chronically elevated stress levels due to these circumstances can have lasting effects on cardiovascular health as well as mental health.

We spoke earlier about ACEs and their impact on one’s likelihood to develop chronic disease in their lifetime. When assessing one’s ACEs score the subject is usually given a questionnaire to respond to. The sections of the questionnaire ask questions about various types of abuse from psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. It also asks questions about the social structure of the child's life: whether a parent was ever neglectful, whether both parents were in the house, and whether or not they had ever considered being adopted by different couples. The worse off your score is the more likely you are to develop a chronic disease later in life.

Why does this all matter?

As we repeatedly discuss health in a holistic and individualized fashion, we cannot deny the importance of advocating for improved health possibilities on a macro level between and within communities. This is particularly true for the black community, as data also suggest that the black community tends to suffer from increased chronic disease and lower life expectancies consistently. Even during the current global pandemic it has been repeatedly shown that black people have been disproportionately affected with worse outcomes and recovery rates. This has also impacted the black community economically as well as almost half of African Americans are struggling to pay their monthly bills due to the virus whether due to job loss or medical expenses (https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/perspective/coronavirus-unequal-economic-toll/).

A word to our fellow healthcare providers

As we continue to provide care based on our patients’ individual needs as opposed to the diagnosis in their medical charts, it is important to remember that we are not all playing with the same deck of cards. Many of our patients will not have the access, the trust, or the understanding to carry out the plan of care we develop with them. Nonetheless, it remains our responsibility to be their advocate regardless and find ways to instill incremental change however that may look.

So when we interact with a patient, particularly one with a different background, are we listening to them and not just hearing them? Are we approaching them with empathy? Are we more eager to learn than we are to teach? Sit with your patients, ask questions about them as a person and not just questions about their injuries, and try to see how they may be affected by things outside of their control.

We admit that we are guilty of turning a blind eye to this issue and our implicit contribution to the challenges posed by social determinants of health. We make no excuses for that and hope that we, as those who swear to do no harm, truly live by that oath for each person that steps foot into our clinics.

HealthAffairs. Health, Income, & Poverty: Where We Are & What Could Help. 2018

Kaiser Family Foundation. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. 2018

Kaiser Family Foundation. Communities of Color at Higher Risk for Health and Economic Challenges due to COVID-19. 2020

NEJM Catalyst. Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). 2017

(https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0312)

Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–1766. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4226

Cockerham WC, et al. The Social Determinants of Chronic Disease. Am J Prev Med 2017; 52(1S1):S5-S12

Ottersen OP, Dasgupta J, Blouin C, et al. The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. Lancet. 2014;383(9917):630‐667. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62407-1

Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, et al. Closing Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet; Volume 372, Issue 9650, 8–14 November 2008, Pages 1661-1669

Sonu S, Post S, Feinglass J. Adverse childhood experiences and the onset of chronic disease in young adulthood. Preventive Medicine 2019: 163-170